01 mar. 2022James Leader: “Poetry is an incredibly dangerous job. It’s up there with firefighting and spying.”

As Expo 2020 Dubai ends, globe-trotting teacher and poet James Leader reflects on his two poems featured in the Luxembourg pavilion and talks about his first solo poetry collection with Editions Phi.

How did you select the poems that were featured in the Luxembourg pavilion at the Expo 2020 Dubai?

I looked at the criteria and thought hard at the beginning. I wondered if I could write a poem to order. I did for my daughter’s poem, but that was an occasional poem. These are not occasional poems. They are more timeless than that. I’ve got 80-90 poems. It wasn’t too difficult to find one that fit.

Were you given prompts or criteria to adhere to?

We were given various themes. One was envisioning the future and that’s what Ode to Gaia is. One was more about interchange between cultures and that’s what Memories of Abu Dhabi is. It was because of the Expo 2020 Dubai that I wrote Memories of Abu Dhabi.

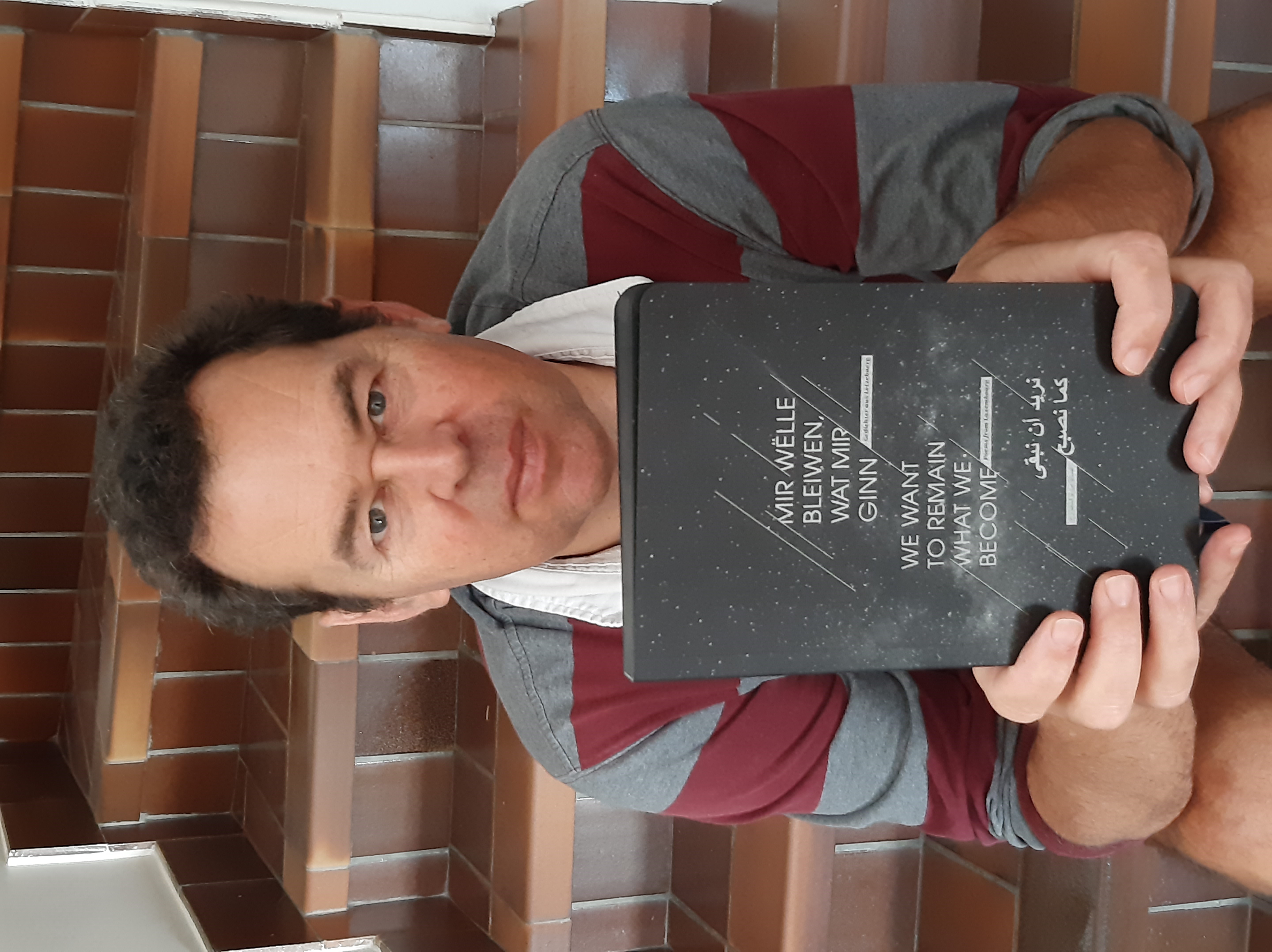

James Leader holds the anthology of poetry from the Luxembourg pavilion at the Expo 2020 Dubai

This latter poem was based on a real experience that happened in a class you taught. Is that right?

I taught in Abu Dhabi for a year and had a wonderful class of eighth grade girls. They were 14 years old and studying Great Expectations. We would act it out and we had a wonderful time. I got sacked from my teaching job because I stood up against the tyrannical headmistress who used to beat the children with a camel stick. The kids knew I was leaving and they had prepared this surprise for my last lesson. The surprise was what happens in the poem – one of them, Hiba, performed a belly dance. She was the highest achieving student who always wanted top marks. She put the music on and the students closed the door. They knew they were doing something haram (forbidden). She started dancing and then the others joined in. It was a magical moment. And it was very close to what happens in the poem Thank you for Dickens, now we will give you some of our culture.

How long ago was this?

That was in 1995. A few years ago, some of the class found me on Facebook. They’re now 38-39, a lot of them are mothers. The end of the poem is about how, in 1995, we couldn’t predict 9/11 was going to happen and that our two civilisations were going to be at war for the next 25 years. The poem is reflecting on that. And it’s about peace breaking out. Now they’re stuck, but someone will find a way of breaking that impasse like Hiba did, by breaking out of the box and breaking into dance.

What was the response in Dubai to your poem?

I would love to know more about how it went down in Dubai and how it was seen but we haven’t been given any of that information. I was a little nervous at the beginning that they wouldn't want to put it on the wall. But they did.

So, that was the first poem. Can you tell us more about Ode to Gaia?

It's about spring and lovers in spring. So in 1820, lovers would go out and pick flowers. Then in 1920, the war has just happened so the young men were dead and in the mud. In 2020, young men are sending requests for nude pictures to girls online. That bond between nature and romance has been broken. The environmental aspect is that once we stop seeing nature as a source of love, a place where you go and pick flowers to give back and forth, we’re alienated from nature. It’s really about love and the environment. In 2120, it’s post-global warming, apocalyptic, there are drones in the air and no flowers at all and everything is desiccated.

What was participating in the Luxembourg pavilion like for you as a poet?

It was nice to be paid for a poem. I got €300 for two poems, which doesn’t sound like a lot but that is a lot of money in poetry circles. Most magazines now don’t pay for poetry, so to get any money at all is very good. Then I got another €300 for the recording. It was another example of Luxembourg’s munificence, which is amazing. They just keep on supporting the arts in a wonderful way.

James Leader and his elder daughter, Anna, in Helsinki (2019)

People will soon be able to read more of your works when you publish your first solo poetry collection with Editions Phi later this year. It’s a great feat and I’m curious to know why you didn’t publish sooner?

I write very slowly. Typically, one or two poems a year for most of my life. Having children and a full-time job really limits the amount of time you have. It took me forever to get anything approaching the number needed. Because you need about 30 minimum for a collection in England. Here it seems to be more. When I finally got there, I didn’t have a structure and I’m a strong believer that poetry collections should have a structure. It took years for that structure to come.

How is the collection structured?

What I have now is something that no-one has ever done, ever, because no-one has ever waited as long as I have waited (laughs). The first poem in this collection goes back to when I was 26, now I’m 57. It’s poetry written over 30 years, which means I’m able to go through the whole biography of my life. And I’m projecting beyond my current age, into old age and death. And I’ve lived all over the place. So, I’ve two structures: geographical and temporal.

Can you tell us more about the individual poems?

It begins with a young man in Spain, Valencia, on his Erasmus, hooking up with a French girl. It’s totally about the glories of Europe. Brits just cancelled Erasmus so it’s a love song that opens up to Europe. It ends with an old love poem where somebody – Milton, in fact – talks about death.

How challenging was it to get published?

When I sent the manuscript with a CV they said they get 1,200 manuscripts per year. And they take three. In England it’s even worse. Having achieved a certain level of recognition, won things and been published, I waited until I had a reasonable chance. But it’s hard.

Did you write any of these poems during the pandemic?

I did. That may be the key – I had so many. I think that’s when I saw the structure emerging. Now I have three collections that are ready to go. I’m publishing the first one first and have more in store.

Editions Phi is a high-quality but small publishing house in Luxembourg. Why not aim for a publisher in the UK or US, where you also have ties?

It’s become more important for me because I think that poetry has become so marginalised. It has become very local. If you’re going to publish, you need to be able to do readings, meet people and know bookstores. Poetry doesn’t have the same amount of clout it did 30-40 years ago. If I was published in England, you wouldn’t get to talk to the bookshops, because what they stock is a tiny selection of poetry, most of it classical or anthologies, with very few contemporary poets. Here I know at least I will be stocked in the bookshops and can do readings.

James Leader gives a poetry reading and creative writing workshop to pupils at the Lycée Aline Mayrisch (2021)

You are an English teacher at the European School II and have taught poetry to adults with Writers Who Talk. What is it that you enjoy about these interactions?

I think poetry is an incredibly dangerous job. It’s up there with firefighting and spying. It is dangerous because poets commit suicide all the time. It’s such an unhealthy thing to do. And to be on your own, in your head, delving into deep emotions is an incredibly stupid and dangerous thing to do. I like the mental stability that you get from doing the job and I love being in contact with people. I get lonely if I’m not with people. I tried full-time writing for a year, here in Luxembourg, for a long hard winter in 2010. It was beyond me.

What are you working towards next?

I’ve written a comic romance novel about the European school. I think it’s good, but it’s been turned down by one publisher in Luxembourg and they didn’t say why. I don’t know if it’s because it’s too risky or not very good. I think that would be interesting for many people in Luxembourg, because it’s about the European Institutions, an Englishman in Luxembourg and the Brexit referendum of 2016. It’s about how a young Englishman comes to Europe, learns what it’s like and has an affair with an older French woman.

Where else can people meet you or read your work?

Hopefully the poetry collection will come out and I’ll do readings and publicity for that. I also just did a big project for the National Library. I worked on James Joyce, because he’s got his centenary. They’ve an exhibition opening in April and I translated a book for them. And I want to start the poetry sessions up again, in the spring. In galleries there’s always a blurb next to the picture that explains it and gives it context. When you read poems, there’s nothing there. You read it and have no-one to talk to about it. Having a framework to share those ideas I think is really nice.

James Leader has published three novels: The Mysteries of Gogos (2011), Chickendance (2014), and The Venus Zone (2017). Find out more about James Leader on his website.

Les plus populaires

- 26 juin. 2024

- 28 juin. 2024

- 05 juil. 2024

- 04 juil. 2024

ARTICLES

Videos

12 juil. 2024TAPAGE avec Chasey Negro

Articles

11 juil. 2024Donato Rotunno, itinéraire d’un producteur européen

Articles

09 juil. 2024